Biblical criticism

- This article is about the academic treatment of the bible as a historical document. This is not the same thing as Criticism of the Bible, which is where criticisms are made against the Bible as a source of reliable information or ethical guidance.

Biblical criticism is "the study and investigation of biblical writings that seeks to make discerning and discriminating judgments about these writings."[1] It asks when and where a particular text originated; how, why, by whom, for whom, and in what circumstances it was produced; what influences were at work in its production; what sources were used in its composition and the message it was intended to convey.

It also addresses the physical text, including the meaning of the words and the way in which they are used, its preservation, history and integrity. Biblical criticism draws upon a wide range of scholarly disciplines including archeology, anthropology, folklore, linguistics, oral tradition studies, and historical and religious studies.

Contents |

Background

Biblical criticism, defined as the treatment of biblical texts as natural rather than supernatural artifacts, grew out of the rationalism of the 17th and 18th centuries. In the 19th century it was divided between the Higher Criticism, the study of the composition and history of biblical texts, and lower criticism, the close examination of the text to establish their original or "correct" readings. These terms are largely no longer used, and contemporary criticism has seen the rise of new perspectives which draw on literary and multidisciplinary sociological approaches to address the meaning(s) of texts and the wider world in which they were conceived.

A division is still sometimes made between historical criticism and literary criticism. Historical criticism seeks to locate the text in history: it asks such questions as when the text was written, who the author/s might have been, and what history might be reconstructed from the answers. Literary criticism asks what audience the authors wrote for, their presumptive purpose, and the development of the text over time.

Historical criticism was the dominant form of criticism until the late 20th century, when biblical critics became interested in questions aimed more at the meaning of the text than its origins and developed methods drawn from mainstream literary criticism. The distinction is frequently referred to as one between diachronic and synchronic forms of criticism, the former concerned the development of texts through time, the latter treating texts as they exist at a particular moment, frequently the so-called "final form", meaning the bible text as we have it today.

History

| Part of a series on |

| The Bible |

|---|

|

| Biblical canon and books |

|

Old Testament (OT) New Testament (NT) Hebrew Bible Deuterocanon Antilegomena Chapters and verses |

| Development and authorship |

| Jewish canon Old Testament canon New Testament canon Mosaic authorship Pauline epistles Johannine works Petrine epistles |

| Translations and manuscripts |

| Septuagint Samaritan Torah Dead Sea scrolls Masoretic text Targums · Peshitta Vetus Latina · Vulgate Gothic Bible · Luther Bible English Bibles |

| Biblical studies |

| Dating the Bible Biblical criticism Higher criticism Textual criticism Canonical criticism Novum Testamentum Graece Documentary hypothesis Synoptic problem NT textual categories Historicity

Internal consistencyPeople · Places · Names Archeology · Artifacts Science and the Bible |

| Interpretation |

| Hermeneutics Pesher · Midrash · Pardes Allegorical interpretation Literalism Prophecy |

| Perspectives |

| Gnostic · Islamic · Qur'anic Christianity and Judaism Biblical law

Inerrancy · Infallibilityin Judaism · in Christianity Criticism of the Bible |

|

· |

Both Old Testament and New Testament criticism originated in the rationalism of the 17th and 18th centuries and developed within the context of the scientific approach to the humanities (especially history) which grew during the 19th. Studies of the Old and New Testaments were often independent of each other, largely due to the difficulty of any single scholar having a sufficient grasp of the many languages required or of the cultural background for the different periods in which texts had their origins.

Old Testament

Modern biblical criticism begins with the 17th century philosophers and theologians - Thomas Hobbes, Benedict Spinoza, Richard Simon and others - who began to ask questions about the origin of the biblical text, especially the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Old Testament - Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy). They asked specifically who had written these books: according to tradition their author was Moses, but these critics found contradictions and inconsistencies in the text that, they claimed, made Mosaic authorship improbable. In the 18th century Jean Astruc, a French physician, set out to refute these critics. Borrowing methods of textual criticism already in use to investigate Greek and Roman texts, he discovered what he believed were two distinct documents within Genesis. These, he felt, were the original scrolls written by Moses, much as the four Gospel writers had produced four separate but complementary accounts of the life and teachings of Jesus. Later generations, he believed, had conflated these original documents to produce the modern book of Genesis, producing the inconsistencies and contradictions noted by Hobbes and Spinoza.

Astruc's methods were adopted by German scholars such as Johann Gottfried Eichhorn (1752–1827) and Wilhelm Martin Leberecht de Wette (1780–1849) in a movement which became known as the Higher Criticism (to distinguish it from the far longer-established close examination and comparison of individual manuscripts, called the lower criticism); this school reached its apogee with the influential synthesis of Julius Wellhausen (1844–1918) in the 1870s, at which point it seemed to many that the bible had at last been fully explained as a human document.

The implications of "Higher Criticism" were not welcomed by many religious scholars, not least the Catholic Church. Pope Leo XIII (1810–1903) condemned secular biblical scholarship in his encyclical Providentissimus Deus;[2] but in 1943 Pope Pius XII gave license to the new scholarship in his encyclical Divino Afflante Spiritu: "[T]extual criticism ... [is] quite rightly employed in the case of the Sacred Books ... Let the interpreter then, with all care and without neglecting any light derived from recent research, endeavor to determine the peculiar character and circumstances of the sacred writer, the age in which he lived, the sources written or oral to which he had recourse and the forms of expression he employed." [3] Today the modern Catechism states: "In order to discover the sacred authors' intention, the reader must take into account the conditions of their time and culture, the literary genres in use at that time, and the modes of feeling, speaking and narrating then current. For the fact is that truth is differently presented and expressed in the various types of historical writing, in prophetical and poetical texts, and in other forms of literary expression."[4]

New Testament

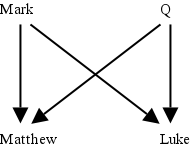

The seminal figure in New Testament criticism was Hermann Samuel Reimarus (1694–1768), who applied to it the methodology of Greek and Latin textual studies and became convinced that very little of what it said could be accepted as incontrovertibly true. Reimarus's conclusions appealed to the rationalism of 18th century intellectuals, but were deeply troubling to contemporary believers. In the 19th century important scholarship was done by David Strauss, Ernest Renan, Johannes Weiss, Albert Schweitzer and others, all of whom investigated the "historical Jesus" within the Gospel narratives. In a different field the work of H. J. Holtzmann was significant: he established a chronology for the composition of the various books of the New Testament which formed the basis for future research on this subject, and established the two-source hypothesis (the hypothesis that the gospels of Matthew and Luke drew on the gospel of Mark and a hypothetical document known as Q). By the first half of the 20th century a new generation of scholars including Karl Barth and Rudolf Bultmann, in Germany, Roy Harrisville and others in North America had decided that the quest for the Jesus of history had reached a dead end. Barth and Bultmann accepted that little could be said with certainty about the historical Jesus, and concentrated instead on the kerygma, or message, of the New Testament. The questions they addressed were: What was Jesus’s key message? How was that message related to Judaism? Does that message speak to our reality today?

The discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls in 1948 revitalised interest in the possible contribution archaeology could make to the understanding of the New Testament. Joachim Jeremias and C. H. Dodd produced linguistic studies which tentatively identified layers within the Gospels that could be ascribed to Jesus, to the authors, and to the early Church; Burton Mack and John Dominic Crossan assessed Jesus in the cultural milieu of 1st Century Judea; and the scholars of the Jesus Seminar assessed the individual tropes of the Gospels to arrive at a consensus on what could and could not be accepted as historical.

Contemporary New Testament criticism continues to follow the synthesising trend set during the latter half of the 20th century. There continues to be a strong interest in recovering the "historical Jesus", but this now tends to set the search in terms of Jesus' Jewishness (Bruce Chilton, Geza Vermes and others) and his formation by the political and religious currents of 1st century Palestine (Marcus Borg).

Methods and perspectives

The critical methods and perspectives now to be found are numerous, and the following overview should not be regarded as comprehensive.

Textual criticism

Textual criticism (sometimes still referred to as "lower criticism") refers to the examination of the text itself to identify its provenance or to trace its history. It takes as its basis the fact that errors inevitably crept into texts as generations of scribes reproduced each other's manuscripts. For example, Josephus employed scribes to copy his Antiquities of the Jews. As the scribes copied the Antiquities, they made mistakes. The copies of these copies also had the mistakes. The errors tend to form "families" of manuscripts: scribe A will introduce mistakes which are not in the manuscript of scribe B, and over time the "families" of texts descended from A and B will diverge further and further as more mistakes are introduced by later scribes, but will always be identifiable as descended from one or the other. Textual criticism studies the differences between these families to piece together a good idea of what the original looked like. The more surviving copies, the more accurately can they deduce information about the original text and about "family histories."

Textual criticism is a rigorously objective discipline using a number of specialized methodologies, including eclecticism, stemmatics, copy-text editing and cladistics. A number of principles have also been introduced for use in deciding between variant manuscripts, such as Lectio difficilior potior: "The harder of two readings is to be preferred."[5] Nevertheless, there remains a strong element of subjectivity, areas where the scholar must decide his reading on the basis of taste or common-sense: Amos 6.12, for example, reads: "Does one plough with oxen?" The obvious answer is "yes", but the context of the passage seems to demand a "no"; the usual reading therefore is to amend this to "Does one plough the sea with oxen?" The amendment has a basis in the text, which is believed to be corrupted, but is nevertheless a matter of judgement.[6]

Source criticism

Source criticism is the search for the original sources which lie behind a given biblical text. It can be traced back to the 17th century French priest Richard Simon, and its most influential product is Julius Wellhausen's Prolegomena zur Geschichte Israels (1878), whose "insight and clarity of expression have left their mark indelibly on modern biblical studies."[7] An example of source criticism is the study of the Synoptic problem. Critics noticed that the three Synoptic Gospels, Matthew, Mark and Luke, were very similar, indeed, at times identical. The dominant theory to account for the duplication is called the two-source hypothesis. This suggests that Mark was the first gospel to be written, and that it was probably based on a combination of early oral and written material. Matthew and Luke were written at a later time, and relied primarily on two different sources: Mark and a written collection of Jesus's sayings, which has been given the name Q by scholars. This latter document has now been lost, but at least some of its material can be deduced indirectly, namely through the material that is common in Matthew and Luke but absent in Mark. In addition to Mark and Q, the writers of Matthew and Luke made some use of additional sources, which would account for the material that is unique to each of them.

Form criticism and tradition history

Form criticism breaks the Bible down into sections (pericopes, stories) which are analyzed and categorized by genres (prose or verse, letters, laws, court archives, war hymns, poems of lament, etc.). The form critic then theorizes on the pericope's Sitz im Leben ("setting in life"), the setting in which it was composed and, especially, used.[8] Tradition history is a specific aspect of form criticism which aims at tracing the way in which the pericopes entered the larger units of the biblical canon, and especially the way in which they made the transition from oral to written form. The belief in the priority, stability, and even detectability, of oral traditions is now recognised to be so deeply questionable as to render tradition history largely useless, but form criticism itself continues to develop as a viable methodology in biblical studies.[9]

Redaction criticism

Redaction criticism studies "the collection, arrangement, editing and modification of sources", and is frequently used to reconstruct the community and purposes of the authors of the text.[10] It is based on the comparison of differences between manuscripts and their theological significance.[11]

Canonical criticism

Associated particularly with the name of Brevard S. Childs, who has written prolifically on the subject, canonical criticism is "an examination of the final form of the text as a totality, as well as the process leading to it."[12] Where previous criticism asked questions about the origins, structure and history of the text, canonical criticism addresses questions of meaning, both for the community (and communities - subsequent communities are regarded as being as important as the original community for which it was produced) which used it, and in the context of the wider canon of which it forms a part.[1]

Rhetorical criticism

Rhetorical criticism of the Bible dates back to at least St. Augustine. Modern application of techniques of rhetorical analysis to Biblical texts dates to James Muilenberg in 1968 as a corrective to form criticism, which Muilenberg saw as too generalized and insufficiently specific. For Muilenberg, rhetorical criticism emphasized the unique and unrepeatable message of the writer or speaker as addressed to his audience, including especially the techniques and devices which went into crafting the biblical narrative as it was heard (or read) by its audience. "What Muilenberg called rhetorical criticism was not exactly the same as what secular literary critics called rhetorical criticism, and when biblical scholars became interested in "rhetorical criticism," they did not limit themselves to Muilenberg's definition. ... In some cases it is difficult to distinguish between rhetorical criticism and literary criticism, or other disciplines." Unlike canonical criticism, rhetorical criticism (at least as defined by Muilenberg) takes a special interest in the relationship between the biblical text and its intended audience within the context of the communal life setting. Rhetorical criticism asks how the text functions for its audience, including especially its original audience: to teach, persuade, guide, exhort, reproach, or inspire, and it concentrates especially on identifying and elucidating unique features of the situation, including both the techniques manifest in the text itself and the relevant features of the cultural setting, through which this purpose is pursued.[13]

Narrative criticism

Narrative criticism is one of a number of modern forms of criticism based in contemporary literary theory and practice - in this case, from narratology. In common with other literary approaches (and in contrast to historical forms of criticism), narrative criticism treats the text as a unit, and focusses on narrative structure and composition, plot development, themes and motifs, characters and characterisation.[14] Narrative criticism is a complex field, but some central concerns include the reliability of the narrator, the question of authorial intent (expressed in terms of the context in which the text was written and its presumed intended audience), and the implications of multiple interpretation (meaning an awareness that a narrative is capable of more than one interpretation, and thus of the implications of each).[15]

Psychological criticism

Psychological biblical criticism is a perspective rather than a method. It discusses the psychological dimensions of the authors of the text, the material they wish to communicate to their audience, and the reflections and meditations of the reader.

Socio-scientific criticism

Socio-scientific criticism (also known as socio-historical criticism and social-world criticism) is a contemporary form of multidisciplinary criticism drawing on the social sciences, especially anthropology and sociology. A typical study will draw on studies of contemporary nomadism, shamanism, tribalism, spirit-possession, millinarianism, etc. to illuminate similar passages described in biblical texts. Socioscientific criticism is thus concerned with the historical world behind the text rather than the historical world in the text.[16]

Postmodernist criticism

Postmodernist biblical criticism treats the same general topics addressed in broader postmodernist scholarship, "including author, autobiography, culture criticism, deconstruction, ethics, fantasy, gender, ideology, politics, postcolonialism, and so on." It asks such questions as, What are we to make, ethically speaking, of the program of ethnic cleansing described in the book of Joshua? What does the social construction of gender mean for the depiction of male and female roles in the bible?[17] In textual criticism, postmodernist criticism rejects the idea of an original text (the traditional quest of textual criticism, which marginalised all non-original manuscripts), and treats all manuscripts as equally valuable; in the "higher criticism" it brings new perspectives to themes such as theology, Israelite history, hermeneutics and ethics.[18]

Notable biblical scholars

- William Albright (1891-1971: seminal figure in biblical archaeology)

- Albrecht Alt (1883–1956)

- Jean Astruc (1684-1776: adapted source criticism to the study of Genesis)

- F. C. Baur (1792-1860: explored the secular history of the primitive church)

- Harold Bloom (b.1930: eminent literary critic, wrote "The Book of J", a reconstruction of the Jahwist source)

- William G. Dever (archaeologist, contributions to the understanding of early Israel)

- Johann Gottfried Eichhorn (1752–1827: applied source criticism to the entire Bible, decided against Mosaic authorship)

- Alvar Ellegård (1919-2008: linguist, has reordered the chronology of the texts of The New Testament.)

- Ludwig Feuerbach (1804-1872: theologian and philosopher)

- Israel Finkelstein (archaeologist, controversial re-dating of remains previously ascribed to King Solomon)

- Richard Elliott Friedman (revised the documentary hypothesis in answer to increasing criticism)

- Hermann Gunkel (1862-1932: the "father" of form criticism, the study of the oral traditions behind the text)

- John Hampden (1595–1643)

- Thomas Hobbes (1588-1679: English philosopher, his Leviathan listed extensive problems with traditional understanding of the authorship of the Bible

- Andreas Karlstadt (1486–1541)

- Yehezkel Kaufmann

- Niels Peter Lemche (b.1945: warns against uncritical acceptance of biblical texts as history)

- Martin Noth (1902-1968: developed tradition history, important work on the origins of the Pentateuch and the Deuteronomistic History)

- Isaac de la Peyrère (1596-1676: wrote on the origins of the Pentateuch)

- Rolf Rendtorff (b.1925: advanced an influential non-documentary hypothesis for the origins of the Pentateuch)

- Friedrich Schleiermacher (1768–1834)

- John Van Seters (b.1935: favours a supplementary model for the creation of the Pentateuch)

- Richard Simon (1638-1712: the Bible consists of numerous archival documents that were rather artificially combined by editors without any addition or intervention in the text)

- Baruch Spinoza (1632-1677: collected discrepancies, contradictions, anachronisms etc. from the Torah to show that it could not have been written by Moses)

- David Friedrich Strauss (1808-1874: influential work on the historical origins of Christian beliefs)

- Johann Jakob Griesbach (1745-1812: Griesbach hypothesis on the origins of the Synoptic Gospels)

- Albert Schweitzer (1875-1965: influential work on the quest for the historical Jesus)

- Thomas L. Thompson (b.1939: criticised Albright's conclusions about archaeology and the historicity of the Pentateuch)

- Julius Wellhausen (1844–1918: influential formulation of the documentary hypothesis)

- Wilhelm Martin Leberecht de Wette (1780–1849: important contributions to the study of Pentateuchal origins)

- Bernard Orchard (1910-2006: modern proponent of the Griesbach hypothesis)

- R. N. Whybray (1923-1997: critiqued the assumptions of source criticism underlying the documentary hypothesis)

See also

- Gospel harmony

- Pentateuchal criticism

- Biblical studies

- The Bible and history

- Biblical archaeology

- Historical method

- Heresy in the 20th century

- Essays and Reviews

- Timeline of the Bible

- Biblical exegesis

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Harper's Bible Dictionary, 1985

- ↑ Fogarty, page 40.

- ↑ Encyclical Divino Afflante Spiritu, 1943.

- ↑ Catechism of the Catholic Church, Article III, section 110

- ↑ Johann Jakob Griesbach (1745–1812) published several editions of the New Testament. In his 1796 edition, he established fifteen critical rules, including a variant of Bengel's rule, Lectio difficilior potior, "the hardest reading is best." Another was Lectio brevior praeferenda, "the shorter reading is best," based on the idea that scribes were more likely to add than to delete. "Critical Rules of Johann Albrecht Bengel". Bible-researcher.com. http://www.bible-researcher.com/rules.html#Griesbach. Retrieved 2010-03-16.

- ↑ David J. A. Clines, "Methods in Old Testament Study", section Textual Criticism, in On the Way to the Postmodern: Old Testament Essays 1967–1998, Volume 1 (JSOTSup, 292; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998), pp. 23–45

- ↑ Antony F. Campbell, SJ, "Preparatory Issues in Approaching Biblical Texts", in The Hebrew Bible in Modern Study, p.6. Campbell renames source criticism as "origin criticism".

- ↑ Bibledudes.com

- ↑ Yair Hoffman, review of Marvin A. Sweeney and Ehud Ben Zvi (eds.), The Changing Face of Form-Criticism for the Twenty-First Century, 2003

- ↑ Religious Studies Department, Santa Clara University.

- ↑ Redaction Criticism.

- ↑ Norman K. Gottwald, "Social Matrix and Canonical Shape", Theology Today, October 1985.

- ↑ M.D. Morrison, "Rhetorical Criticism of the Hebrew Bible"

- ↑ Johannes C. De Klerk, "Situating biblical narrative studies in literary theory and literary approaches", Religion & Theology 4/3 (1997)

- ↑ Christopher Heard, "Narrative Criticism and the Hebrew Scriptures: A Review and Assessment", Restoration Quarterly, Vol. 38/No.1 (1996)

- ↑ Frank S. Frick, Response: Reconstructing Israel's Ancient World, SBL

- ↑ David L. Barr, review of A. K. M. Adam (ed.), Handbook of Postmodern Biblical Interpretation, 2000

- ↑ David J. A. Clines, "The Pyramid and the Net", On the Way to the Postmodern: Old Testament Essays 1967–1998, Volume 1 (JSOTSup, 292; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998)

Further reading

- Barton, John (1984). Reading the Old Testament: Method in Biblical Study, Philadelphia, Westminster, ISBN 0-664-25724-0.

- Birch, Bruce C., Walter Brueggemann, Terence E. Fretheim, and David L. Petersen (1999). A Theological Introduction to the Old Testament, ISBN 0-687-01348-8.

- Coggins, R. J., and J. L. Houlden, eds. (1990). Dictionary of Biblical Interpretation. London: SCM Press; Philadelphia: Trinity Press International. ISBN 0-334-00294-X.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2005). Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why. HarperSanFrancisco. ISBN 0-06-073817-0.

- Fuller, Reginald H. (1965). The Foundations of New Testament Christology. Scribners. ISBN 0-684-15532-X.

- Goldingay, John (1990). Approaches to Old Testament Interpretation. Rev. ed. Downers Grove, IL, InterVarsity, ISBN 1-894667-18-2.

- Hayes, John H., and Carl R. Holladay (1987). Biblical Exegesis: A Beginner's Handbook, Rev. ed. Atlanta, GA, John Knox, ISBN 0-8042-0031-9.

- Knight, Douglas A., and Gene M. Tucker, eds. (1993). To Each Its Own Meaning: An Introduction to Biblical Criticisms and Their Applications, Louisville, KY, Westminster/John Knox, ISBN 0-664-25784-4.

- Rogerson, John (1984). Old Testament Criticism in the Nineteenth Century, SPCK, ISBN 0-2810-4094-X.

- Morgan, Robert, and John Barton (1988). Biblical Interpretation, New York, Oxford University, ISBN 0-19-213257-1.

- Soulen, Richard N. (1981). Handbook of Biblical Criticism, 2nd ed. Atlanta, Ga, John Knox, ISBN 0-664-22314-1.

- Stuart, Douglas (1984). Old Testament Exegesis: A Primer for Students and Pastors, 2nd ed., Philadelphia, Westminster, ISBN 0-664-24320-7.

- Shinan, Avigdor, and Yair Zakovitch (2004). That's Not What the Good Book Says, Miskal-Yediot Ahronot Books and Chemed Books, Tel-Aviv

External links

- David J. A. Clines, "Possibilities and Priorities of Biblical Interpretation in an International Perspective", in On the Way to the Postmodern: Old Testament Essays 1967–1998, Volume 1 (JSOTSup, 292; Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 1998), pp. 46–68 See Section 6, Future Trends in Biblical Interpretation, overview of some current trends in biblical criticism.

- Philip Davies, review of John J. Collins, "The Bible after Babel: Historical Criticism in a Postmodern Age", 2005 Reviews a survey of postmodernist biblical criticism.

- Allen P. Ross (Beeson Divinity School, Samford University), "The Study of Textual Criticism" Guide to the methodology of textual criticism.

- Yair Hoffman, review of Marvin A. Sweeney and Ehud Ben Zvi (eds.), The Changing Face of Form-Criticism for the Twenty-First Century, 2003 Discusses contemporary form criticism.

- Exploring Ancient Near Eastern Civilizations on the Internet Introduction to biblical criticism